The Life Cycle of a Water Well

The average water well outlives the contractors who work on it. Between when it is drilled and when it is shut down, any number of people will service, maintain, monitor, repair, and replace components of the well – and, it is hoped, they will do so in a way that fosters sustainability for the well and for the ground water it taps into.

To achieve an industry standard in keeping with today’s expectations and requirements takes teamwork over decades and an accurate, well- maintained reporting system. Ultimately, it means thinking about wells in terms of stewardship over the long term, which is the driving goal behind Jim Clark’s Water Well Life Cycle project.

“The idea is to enlighten those who work on wells to all of the steps involved from start to finish and how teamwork is needed to keep the life-cycle process going successfully and smoothly,” says Clark, a director of the British Columbia Ground Water Association (BCGWA). He has drilled wells for more than 40 years in B.C.’s Fraser Valley, an area of significant agricultural importance.

Clark points out that very few contractors have the knowledge, specialized equipment and skilled staff to complete all steps required through a well’s life and that the average well will outlive those who work on it. A good paperwork trail is crucial to maintain a knowledgeable pathway and makes it easier for a contractor to understand how the well was constructed, what equipment has been installed “down hole,” and what maintenance activities have been performed to date.

“All commercial well owners need to be encouraged to keep a file and all contractors that visit need to document what they do,” Clark says. “The life cycle of a well stretches for years. A well may only expect one major visit per 10 years.”

A solid case for long-term monitoring

Establishing early benchmarks, specifically for static and pumping water levels, flow rate, and specific capacity, is critical for tracking well performance and will help to alert the well owner of trouble long in advance, Clark says. He estimates less than 10 per cent of irrigation well owners know what their pumping level is and that few of these wells are fitted with sounding tubes to enable technicians to record those levels.

“Without this simple tube and wellhead access, the well owner is headed for an unexpected meltdown as his pumping level slowly creeps down to the pump, often over many years,” he says.

Then, likely mid-August when temperatures are high and crops are wilting in the fields, there is an urgent need to initiate redevelopment, or in some cases, replace the well.

“Often, in a panic, patchwork is done to the system to try and nurse it through until the off-season,”

Clark says. “Usually, most of the money spent on patchwork by the well owner is lost, and there is some degree of crop loss, hitting the farmer hard in the pocket.”

A well owner or driller may avoid these often devastating situations through two simple steps: recording the static water level, pumping water level and flow rate when the well is new, and tracking these three measurements occasionally over the years.

“In most cases, the well owner will have several years to react to problems that are manifesting in his well, while avoiding costly panic patch jobs and crop loss,” Clark says.

Clark points to an evolving opportunity for contractors in alerting their customers to these potential problems and offering to set up monitoring programs.

“We need to understand the well owner will know very little about potential well problems,” he says.

The well owner without wellhead access is doomed to make repairs under downtime, most likely during critical crop-growing season in the case of irrigation wells, costing the farmer a “triple whammy” of money lost to patchwork, increased repairs, possible well replacement and lost crops.

“There are far too many production well users who rely totally on ground water to keep their business alive and who have no clue if the gas tank is full, empty, or has a hole in it,” Clark says. “Monitoring brings everything into view, good or bad, and should a well owner go for 40 years with no major trouble, at least a little monitoring over the years has given him peace of mind.”

“Setting up monitoring programs is an easy way for pump companies to expand their horizons. This strengthens ties to your customer, almost ensuring pump sales and future service work,” Clark says.

He further explains that monitoring programs for most existing wells would likely see frequent readings in the first couple of years to establish good data benchmarks. If levels are stable, the number of readings can likely be reduced to one a year, and a year or two can even be skipped.

High cost of not monitoring

Many well owners shy away from monitoring their wells because of cost. Clark says that those who don’t monitor often pay a higher price when faced with unexpected downtime, which often comes at the worst time for their operations.

“As the industry has evolved, smart operators turned ‘emergency downtime’ into ‘preventive maintenance,’ which is done at least once annually when a piece of equipment is shut down for overhaul,” Clark says. “Preventive maintenance sees parts swapped out that may or may not need to be. The idea is not to take chances and to cover the board.”

“By monitoring a well, you can identify exactly what needs servicing, which is defined as ‘predictive maintenance,’ ” Clark says. “This takes all the guessing out and allows the well owner to schedule repairs at opportune times with the problem already identified.”

Being able to predict maintenance saves huge costs, every time, especially when crop loss is considered.

Taking a big-picture view

Over the years, the refinement of the various skilled trades within the water well industry means it is very difficult and unlikely for one person to maintain a high level of knowledge of all those trades, Clark says. As a result, communication among the contractors has become increasingly important.

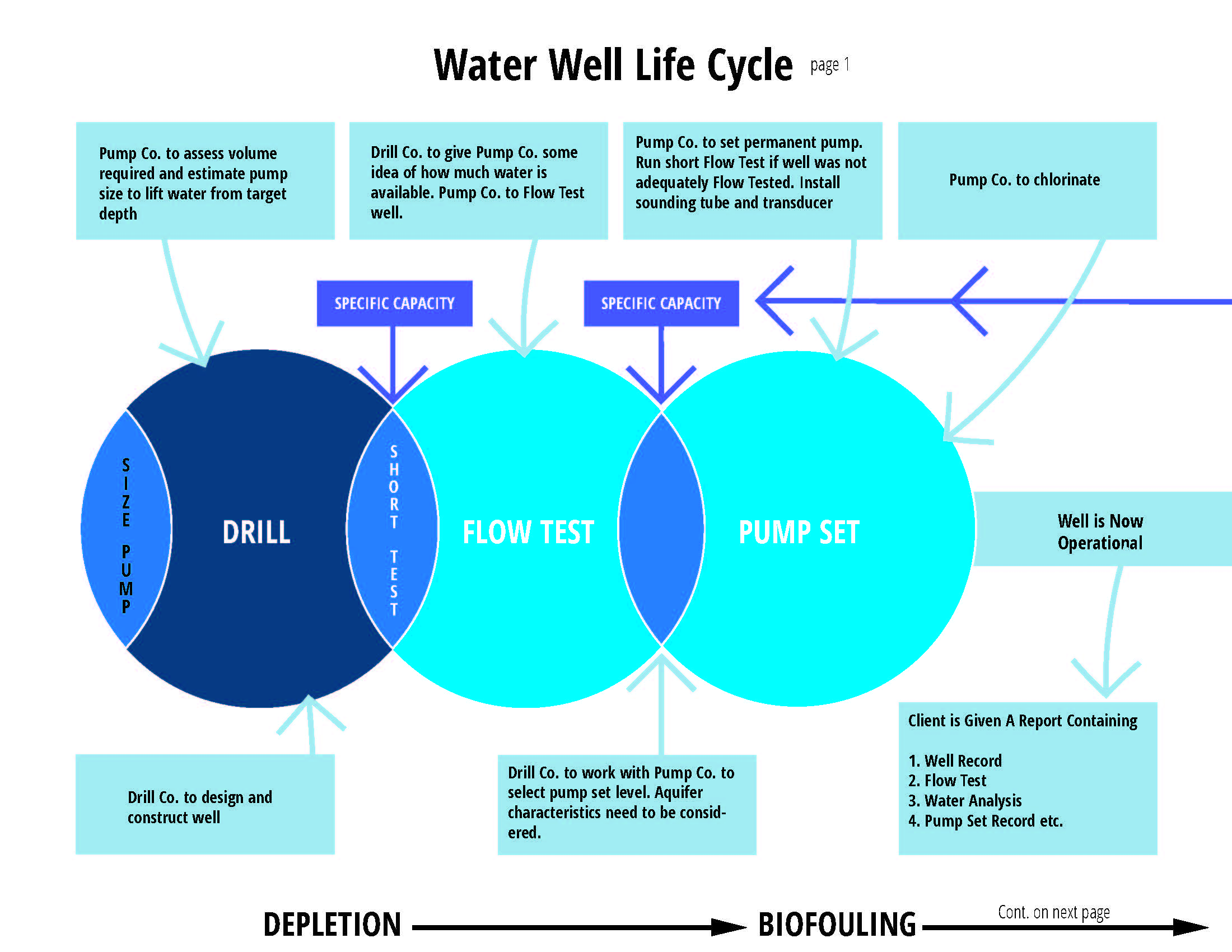

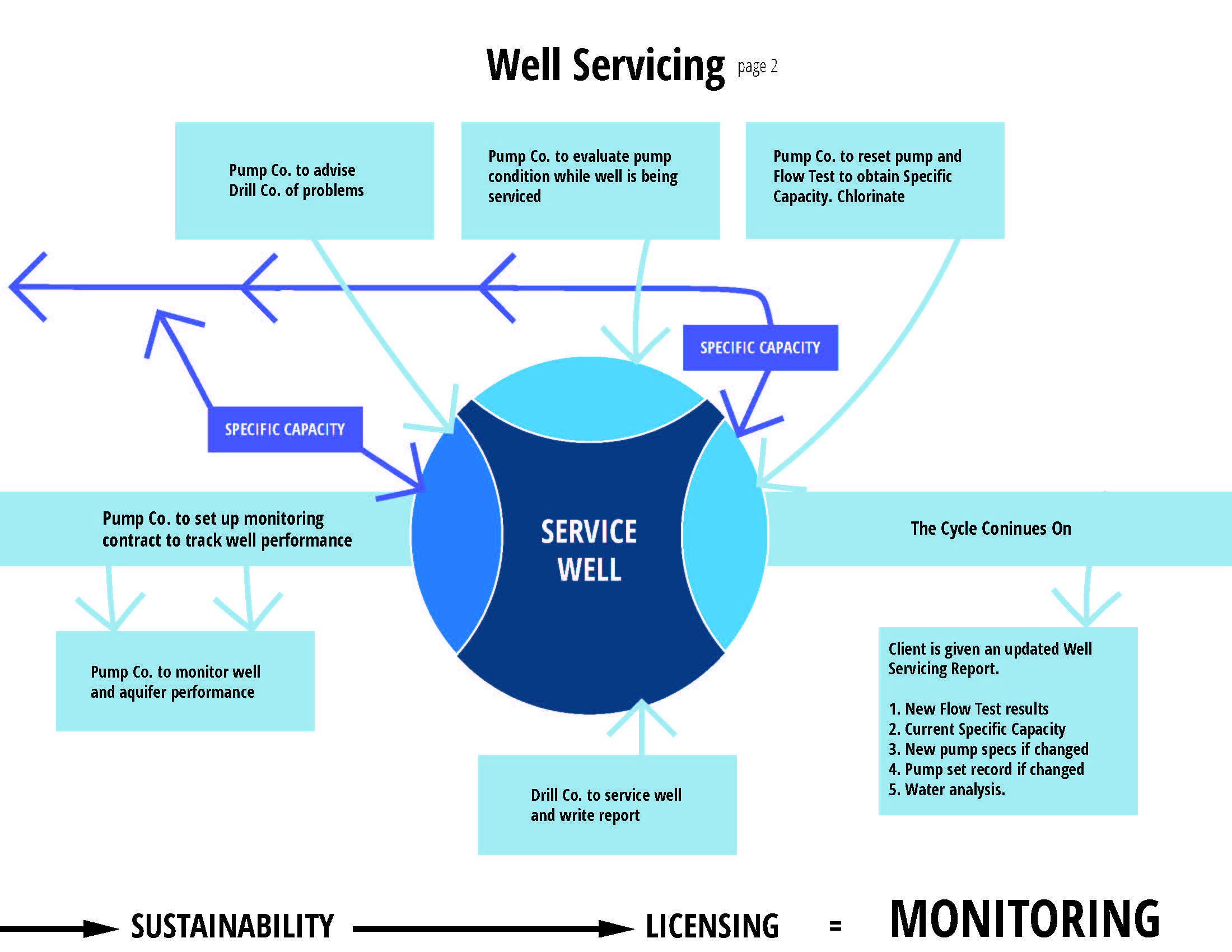

To illustrate the life cycle of a well and the importance of record keeping and teamwork among the various contractors, he has created a diagram. Clark’s Water Well Life Cycle graphic aims to highlight contractors’ individual roles and reveals opportunities where they may want to expand.

“Most importantly, contractors need to be careful they don’t step out too far beyond their abilities,” he says. “Better contractors define their boundaries. It’s best to go in and do what you can do and pass the torch to another contractor when necessary. This leads to teamwork, which will enhance the outcome of the work for everyone involved.”

A key point is the line of arrows that runs backwards across the diagram from where the service tech may first discover trouble, Clark says.

“When dealing with a problem, a service man will always look back to the baseline data. Looking for the original specific capacity is often the carrot you are looking for,” he says.

To quickly assess the well’s condition, the service tech needs wellhead access to attain a current water level and specific capacity, and then relate it to the original specific capacity.

Measuring specific capacity is standard practice for calculating and tracking well performance, says Kathy Tixier, the BCGWA’s managing director. It is calculated as the flow rate divided by the drawdown in water level in the well, or the difference between the static water level and the pumping water level.

“It is like the bang for your buck,” she says, explaining the amount of flow produced is the “bang” and the unit drop in water level is the “buck.”

“As well efficiency drops over time, so too does specific capacity,” Tixier says. “Tracking changes in specific capacity can help well owners schedule maintenance activities when they are needed and when operationally convenient.”

When the wellhead is easily accessed, well-informed decisions can be made. However, when there is no wellhead access, it can be a real downer, Clark says.

“If wellhead access is not available, everything comes to a halt and lesser quality decisions are made,” he says.

“Most of my job is to drive around and look at things. When I respond to a troubled well call that has good wellhead access, I jump out of my truck and run my sounder down and often have a good handle on the problem within minutes.”

When there is no wellhead access, he drives away far less informed about the problem.

“Guessing and assuming can often lead to poor decisions that cost everyone involved time and money,” he says.

Those expensive, time-consuming decisions are simply not sustainable.

This article appeared in the Summer 2016 issue of Ground Water Canada and is reprinted by permission. The BCGWA would like to acknowledge Ground Water Canada for this privilege.